Having in my time bought a few too many second hand books that turned out to disappoint, it’s rewarding when the reverse happens.

Some years ago, I forget where, I picked up for a quid a damp-buckled copy of Stephen Spender’s Life and the Poet, 1942, in which Spender attempts to reposition the role of the progressive artist and intellectual post-Spain, post-Popular Frontism. This was published by Secker & Warburg as Searchlight Book No 18, a series edited by George Orwell and T R Fyvel, billed as broadly popular, patriotic and anti-fascist. (Of the 17 projected titles listed here, only ten actually appeared before the printer’s paper stock ran out.) Searchlight Books were hardback with a dust jacket, but mine has paper covers, so must be a review copy.

Some years ago, I forget where, I picked up for a quid a damp-buckled copy of Stephen Spender’s Life and the Poet, 1942, in which Spender attempts to reposition the role of the progressive artist and intellectual post-Spain, post-Popular Frontism. This was published by Secker & Warburg as Searchlight Book No 18, a series edited by George Orwell and T R Fyvel, billed as broadly popular, patriotic and anti-fascist. (Of the 17 projected titles listed here, only ten actually appeared before the printer’s paper stock ran out.) Searchlight Books were hardback with a dust jacket, but mine has paper covers, so must be a review copy.

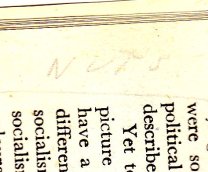

And indeed, a reviewer has made his or her reactions known in some enjoyably bad tempered annotations, summarised inside the front cover:

Mr Spender wrote but apparently never went “Forward from Liberalism”. This is a wretchedly poor book, illogical, disconnected, apologetic & generally unsound.

Life and the Poet does indeed seem hastily shoved together, sloppily thought through and in places just badly written. Spender dedicates it to “Young Writers in the Armed Forces, Civil Defence and the Pacifist Organisations of Democracy”, which by covering all options avoids offence, but indicates something of the hand wringing equivocation he feels obliged to deliver.

Life and the Poet does indeed seem hastily shoved together, sloppily thought through and in places just badly written. Spender dedicates it to “Young Writers in the Armed Forces, Civil Defence and the Pacifist Organisations of Democracy”, which by covering all options avoids offence, but indicates something of the hand wringing equivocation he feels obliged to deliver.

“Before finishing the last chapter of this book,” he confesses, “and while revising the first five chapters, I have already been called up into the Fire Service. Yet I may stimulate in the minds of a few people the urgent necessity of a faith in poetry, or, rather, the poetic attitude …”

Our reviewer is not impressed by this excuse. Here are a few passages he/she found objectionable, with his/her reactions transcribed in italics:

Spender: ‘Generally unsound’

Without saying that Tolstoi, Turgenev or Henry James were socialists, one might draw revolutionary political conclusions from the life which they describe in their novels. Yet to believe … that the true picture of life in fiction today would inevitably have a socialist political implication is entirely different from preaching that … novels should preach socialism and see everything through red-coloured spectacles.

NUTS

In the case of a really great novelist or poet there might even be no difference, because his observation and his conclusions would be indivisible. But in the case of those lesser artists, there is a tremendous difference.

If the political conclusions were sound then the Novel will be too. The rest of Spender’s thesis is nonsense.

Listening to these [Left Wing] lectures on literature, it seemed to me that the principles were right, but their application was always wrong.

Well what the hell?

The ultimate aim of politics is not politics, but the activities which can be practised within the political framework of the State. Therefore an effective statement of these activities – such as science, art, religion – is in itself a declaration of ultimate aims around which the political means will crystallise.

Aim? Politics has no aim, any more than evolution has.

So the political agitator is driven to deny that there is anything in life outside the struggle for power … Therefore you must pretend that everyone on your own side who is killed is a hero gladly giving his life for your cause without indulging in any feelings as a separate individual which might be irrelevant. Indeed, you go on to deny that anything in the nature of an individual really exists or has ever existed.

Oh do I?

Politics then become the only reality, and … [Artists, thinkers and scientists] make a merit of stifling the light that is in them: to become scientists who deny that scientific enquiry can ever be objective, poets who deny their own individuality, who show no curiosity about man’s situation in the whole of life and the universe, novelists who have no interest in human beings except to prove that one race or class is superior to others.

Mr Spender appears to have all the intellectual’s concern for his own piddling little individuality. What does he mean by superior? Dominant? Obviously no class is “Better” – No one suggests any one is.

Political evils must be met by other, greater political evils until the war is won. Yet, just because of this, it is all the more important that the “happy few” who uphold values of art, poetry and science should state as clearly as they can what the function of those values in life is, in order that new social patterns may grow around such an understanding.

Ha! Ha! Spender & Co, world-lovers & leaders.

Politicians establish a Sabbath of institutions which petrify, until at last they are shattered by revolutions. Yet to the revolutionaries, who are also politicians, Man … is still only made for their new Sabbath, which, they are determined, differs from the old Sabbath in that it will never be destroyed.

Nonsense. If Mr S will tilt at Marxists he should get to know some Marxism, which denies the possibility of a fixed, static, immutable policy.

What is important is Man. The creative mind must never entirely subscribe to any kind of Sabbath – Pharisaic, Jewish, Christian, Roman, Communist or British Imperialist.

What is important is Man. The creative mind must never entirely subscribe to any kind of Sabbath – Pharisaic, Jewish, Christian, Roman, Communist or British Imperialist.

How nice for the creative mind.

Part way through chapter two our annotator loses patience with the chore of annotation, but has made his or her position pretty clear. The book’s owner did not think to add a name, so who was this irascible Marxist?

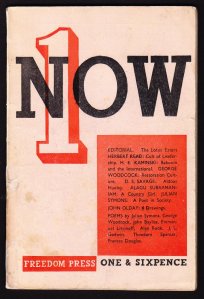

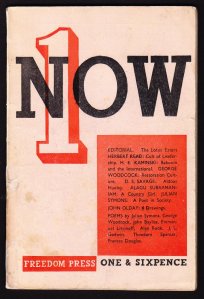

As it happens, the sentiments chime rather well with “A Poet in Society,” a review of the book by Julian Symons in the first issue (1943) of the second series of Now, the anarchist political-literary review edited by George Woodcock at Freedom Press. (See here for another aspect. As it also happens, the handwriting of the annotations is not incompatible with the very few samples of Symons’s writing I can see online, though I can’t pretend that the similarities are absolutely conclusive.)

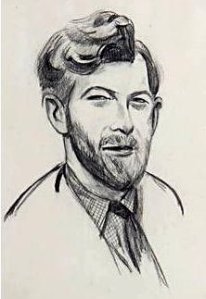

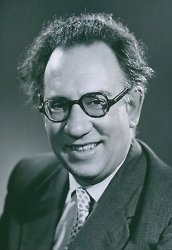

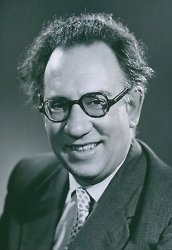

Symons: acerbic

Symons is best known as a writer of crime fiction in later life, but was then the founder of Twentieth Century Verse, an independent Marxist (usually tagged a “Trotskyist”), and a reviewer of clinical and acerbic penetration. While Woodcock aimed to align the new series of Now with an “anarchist point of view,” contributors did not necessarily “subscribe to anarchist doctrines,” and in an editorial intro he carefully separates himself from the “hard things” that Symons has to say, defending “a certain virtue” in Spender’s “doubt of the value of politics as a means of social action.” Maybe he was anxious to avoid offending Orwell, later a contributor to the magazine.

In his review Symons tackles both Life and the Poet and Spender’s latest poetry collection, Ruins and Visions. The poems he finds “fine” and “moving”, but with Life and the Poet he finds himself “in violent disagreement,” denouncing it as “a high, thin and cloudy view of the poet’s nature and function,” marked by “the confusion of thought and frequent clumsiness of phrase which we have learned to expect and regret … Sometimes,” he adds, “this leads him into sentimental rubbish … It is impossible to comment usefully upon writing at this level.”

His critique follows the annotations at a distance while, naturally enough, losing some of the immediacy of his anger. One or two of our annotated passages in particular are fastened on. Spender, who believes in no absolute, is criticised for setting up “the creative mind” (see the final passage above) as a kind of absolute. The fourth annotated passage above, on the “ultimate aim of politics,” comes in for particular scrutiny:

His critique follows the annotations at a distance while, naturally enough, losing some of the immediacy of his anger. One or two of our annotated passages in particular are fastened on. Spender, who believes in no absolute, is criticised for setting up “the creative mind” (see the final passage above) as a kind of absolute. The fourth annotated passage above, on the “ultimate aim of politics,” comes in for particular scrutiny:

Man is a social animal: and his creative activities – “activities which can be practised within the political framework of the State” – are part of his social life. It follows that to talk about a statement of artistic aims round which political means will crystallise is to talk nonsense. A new view of society must precede a new view of art: society fashions art, art does not create a society. It is therefore a delusion to believe that any artistic aims are ultimate, since no state of society is ultimate: artistic aims are instead fashioned out of the social life of the time, which is in turn influenced by the tradition of social life and art which it has accepted as a heritage. “Eternal aspirations,” loneliness, and yes, the “creative mind” itself vary in form with the society that contains them. A society gets the art it deserves.

The heavy stress placed on “life” in this book is occasioned by an irrational dislike for the logic which binds the poetry written today inside our routine of living; a routine which exists as much for those who try to be “free” and who write from a position of freedom which is in fact false, as for those who are consciously and even willingly bound.

This is all excellent common sense, and seems to me highly relevant to today’s facile, commodified and over-valued art scene, still lubricated by persistent notions of art and poetry as magical, “alternative,” special or visitation from without.

Symons was surely one of the sharpest minds at work on the Left during this period. In a contribution to Now 5 on “The End of a War: 8 Notes on the Objective of Writing in our Time,” he references, interestingly, Wyndham Lewis’s Men Without Art, making entirely valid use of the perceptions of a writer working “from an attitude very different from mine.” (Symons knew Lewis well, and respected him.) In Now 6 his demolition of Cyril Connolly (“The Condemned Playboy”) is a pleasure to read.