Join 351 other subscribers

Recent posts

- Russell Quay, skiffle painter

- Easter under a cloud

- Mississippi to Cambridge – Marie Battle Singer

- Death, grief and Bacon

- Bow down mister!

- Eileen Agar’s fish tank

- Geoffrey Hill fails the bookcase test

- Nostalgia for no known face: the poems of Cameron Cathie

- Empathetic embodiment: the dance of Roger Pryor Dodge

- Out of the ordinary: the paintings of Mabel Layng

- Blast mask

- Depiphanies

- We look for the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come

- The silence of the baa-lambs

- Red white and blue retirement

Categories

Aerschot Performance Division animation Annesley Tittensor art artwork Burns Singer cartoons David Gascoyne fiction George Barker Gordon Wharton Helen Saunders Jack Clemo James Fox Jessica Dismorr Lawrence Atkinson music New Apocalypse photos poetry Robert Colquhoun Robert MacBryde sculpture T S Eliot Uncategorized Vorticism William Empson W S Graham Wyndham Lewis

Tags

abstraction Aleister Crowley anarchism art Arthur Berry Barbara Hepworth Blast British Masters Burns Singer Cambridge Charles Causley Christmas Christopher Logue Christopher Wood collage Dada David Bomberg David Jones decollage Delancey Drummond Allison Dylan Thomas Easter eBay Edwin G Lucas Ezra Pound Francis Bacon Gaudier-Brzeska George Woodcock Grace Pailthorpe Henry Treece Jacob Epstein James Joyce Jankel Adler John Minton John Shelton Keith Vaughan kitsch L S Lowry Mander Centre Mandergate Mervyn Peake Michael Ayrton neo-romanticism New Art Gallery Walsall painting Paul Nash Paul Potts photos Picasso poetry portrait public art RBS resurrection Reuben Mednikoff Robert Colquhoun Robert MacBryde Rock Form sculpture situationist Stanley Spencer Stephen Spender surrealism Tambimuttu Tate Britain The Two Roberts T S Eliot Vorticism W H Auden William Roberts Wolverhampton Wolverhampton Art Gallery W S Graham Wyndham LewisLinks

- Burma & Myanmar Philately My other other blog: Burma, stamps, postal history

- My artwork

- This Re-illuminated School of Mars – my other blog. Auxiliary forces and other aspects of a Nation under Arms in the Great War against France

Archives

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- July 2020

- April 2020

- December 2019

- October 2019

- July 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- December 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- June 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

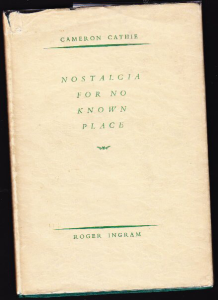

Nostalgia for no known face: the poems of Cameron Cathie

I n among my stacks of unread or under-read books (they’ve peaked exponentially under lockdowns) is a slim, beige volume of verse – Nostalgia for No Known Place by Cameron Cathie, published in 1938 by Roger Ingram. (I know nothing about this publisher except that by the ‘forties their output had shifted to reprints of classics.) This modest collection of some two dozen poems comes in a numbered edition of 250, the front jacket flap bearing a tepid endorsement by no less than Richard Church – ‘I have found much in your work to interest me … Good fortune to your first book’ – which doesn’t bode well. However, an inside note reveals that some of the poems had previously been published in Comment, the busy little mag edited from 1935 to 1937 by Sheila MacLeod and Victor Neuberg, whose contributors (according to Miller and Price’s invaluable British Poetry Magazines 1914-2000) included Dylan Thomas, Ruthven Todd, G S Fraser etc, which is more like it.

n among my stacks of unread or under-read books (they’ve peaked exponentially under lockdowns) is a slim, beige volume of verse – Nostalgia for No Known Place by Cameron Cathie, published in 1938 by Roger Ingram. (I know nothing about this publisher except that by the ‘forties their output had shifted to reprints of classics.) This modest collection of some two dozen poems comes in a numbered edition of 250, the front jacket flap bearing a tepid endorsement by no less than Richard Church – ‘I have found much in your work to interest me … Good fortune to your first book’ – which doesn’t bode well. However, an inside note reveals that some of the poems had previously been published in Comment, the busy little mag edited from 1935 to 1937 by Sheila MacLeod and Victor Neuberg, whose contributors (according to Miller and Price’s invaluable British Poetry Magazines 1914-2000) included Dylan Thomas, Ruthven Todd, G S Fraser etc, which is more like it.

So who was Cameron Cathie? I can’t say I’ve found that much. Born in Finchley in 1910 to parents who were both musicians, he changed his name by deed poll in 1942 to Dermot Cathie, but seems to have been known in full as Dermot (or Diarmid) Cameron Cathie. Early in the war he served in the Friends’ Ambulance Unit, so I’m assuming that he was a pacifist and conscientious objector. His life’s work was in acting. He first trod the boards in 1932, became a stalwart of the BBC rep company, and produced a stage version of Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler in 1942.

The regretful homesickness of the title of Cathie’s little book is at one remove, the ‘no known place’ being an Ireland that London-born Cathie cannot truly reclaim. In the title poem an Irish voice imagines that lost landscape while mooching round Kensington Gardens and indulging in angsty theatrical metaphors for time, love etc.

There are faults, of course. His musings, sometimes a bit indisciplined, can veer off into the inconsequential, and the significances of what are clearly intended as significant moments are not necessarily felt by the reader. Cathie’s occasional habit of bathetically juxtaposing the archaic and the banal, like this –

O Love, Love, how cold thou canst be

at four a.m., on deck or in the saloon!

– is not as witty as he thinks, and can come across as showy, annoying. His style is sometimes sometimes sunk by appended lyrical platitudes such as:

But love / is in no need of gesture

or

Count not the daffodils / Till they bloom

Quite. Elsewhere, in contrast, it’s too jerky, with a few awkward elisions that could even be typo’s for all I can tell.

But despite the patchiness of the poems, I invested my humble fiver in his book because I like his voice, which is wry, cynical, with a slightly offbeat, young man’s weariness. To be fair, Cathie is at least a half decent poet, and at times it all works quite well, as here from ‘Rose and Crown’:

in a tankard

tanging and heady

with iridescent gas …

… penultimate as last orders

certain as time gentlemen please

there offered a moment

untouchable behind him behind

glass doors that swing no more

and he’s alone at three

in windshining autumnal

verisimilitude of streets.

Those were the days, when the pubs closed after lunch. Let’s finish with more than an excerpt, the full two stanzas of ’The Gentle Wind Doth Move Silently, Invisibly’ (title borrowed from William Blake’s ‘Love’s Secret’):

My loins girded with nervous tension,

temples and hair with fillet of steel;

spirit plashing unconscious shallows;

I come between fragments of speech from afar.

Your eyes trace the slow bewildering trajectory

till I look on the words’ source, moving me, gleaming anew:

stares from your eyes, stares ecstasy back on me,

come between fragments of speech from afar.

I rather like this, despite the arbitrary punctuation. (Does ‘I come’ mean here what it seems to mean? Maybe. Sex is happily present among these poems.)

Classy special effect from ‘They Came from Beyond Space’

Post-war, Dermot Cathie moved via stage and radio to film, with a string of smallish roles. His chief Google fame is now the distinctly minor part of Peterson in They Came from Beyond Space, Freddie Francis’s laughable (read ‘cult’) Twickenham horror film of 1967. (So far down the cast list is Peterson that I can’t pick out Cathie in the online stills.) A brief cv, in Radio Who’s Who for 1947, concludes with this: ‘Having neither hobby nor club, he says he anticipates an early death’. Happily, he did not die until 1993, aged 82. His cv, sadly, has no publicity mugshot with it.

There’s too much poor and mediocre poetry littering this world (I include my own attempts). But if Cameron/Dermot Cathie’s poems are clearly less than perfect, they’re a long way short of piffle. His endeavours in poetry and short story writing may have petered out by the start of the War, but it would be a shame if they were now to shuffle off into complete oblivion. Hence this post. I haven’t yet been able to put a face to him – ironic, for an actor – but I’d like to imagine that I can remember one.