As an addendum to my previous post on the painter Gerald Wilde (go here), I give you the best part of an article on Wilde by Joyce Cary, author of The Horse’s Mouth and creator of the incorrigible, penniless and visionary painter Gulley Jimson, with whom Wilde fiercely identified.

This appeared in Vol 3 No 2 (1956) of Nimbus, the literary review created by Tristram Hull, and edited at the time by him and David Wright. I’ve omitted the more general passages where Cary expands on the issue of artistic originality and so forth, which, to be honest, are pretty skippable. This piece is not excerpted in the 1988 October Gallery monograph on Wilde, and I don’t see it online, so here we are. Included here are the four illustrations: a fine photo of Wilde by Gilbert Cousland, and three black and whites of Wilde paintings, one then owned by Cary.

This appeared in Vol 3 No 2 (1956) of Nimbus, the literary review created by Tristram Hull, and edited at the time by him and David Wright. I’ve omitted the more general passages where Cary expands on the issue of artistic originality and so forth, which, to be honest, are pretty skippable. This piece is not excerpted in the 1988 October Gallery monograph on Wilde, and I don’t see it online, so here we are. Included here are the four illustrations: a fine photo of Wilde by Gilbert Cousland, and three black and whites of Wilde paintings, one then owned by Cary.

Here, Cary’s startling characterisation is of an artist as a complete original, beyond tradition, outside all context, and so an apparition, a revenant, a dweller in another world. One wonders how Wilde felt, reading about himself as a rattling spectre … But it’s a fine piece of writing, about a great and neglected painter. The Art UK site now shows just five paintings by Wilde in public collections, two owned by Oxford colleges. It’s better than none.

(Throughout the original, oddly, Gulley is spelt as “Gully,” which I’ve corrected. A note on personalities mentioned – the Davins: Dan and Win Davin. Dan Davin, author, then working for Oxford UP. Winnie Davin was Cary’s close friend and literary executor. Ronnie Syme: Ronald Syme, classicist and historian, then at Brasenose, Oxford. Father Gervase Matthews: Gervase Mathew[sic], Dominican theologian, Oxford lecturer.)

JOYCE CARY

GERALD WILDE

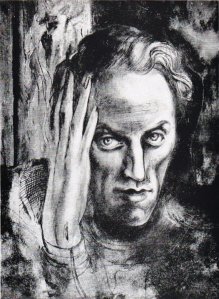

The first time I met Gerald Wilde was, I think, about 1949, in Oxford, at the Davins’. It was late in the evening. There was a crowd of people in the room, Ronnie Syme, the historian, was one, and I think Louis MacNeice was another, certainly I know I was sitting by the fire conversing on some historical matter with Father Gervase Matthews, when I heard a queer noise and saw in the middle of the room, a figure strange even in that gathering place of poets and professors, of dreamers in all dimensions.

Gerald Wilde

At first glance, in the dim light, Wilde seemed like a spectre. His long, dead-white face with its hollow cheeks was like a mask of bleached skin on a skull, his arms seemed but bones, hanging loosely in the sleeves of an enormous coat whose crumpled folds gave no room for flesh. The arms, too, were extremely long, so that the bony hands almost touched the floor. It was as if this skeleton had but half risen from the grave.

All this figure was in violent and continuous agitation, and with a movement that seemed by itself preternatural. It was this shivering, shaking which, more than anything, gave, at the moment, the sense of visitation from another world. Ghosts in fiction are still dignified appearances, they either stand still like Hamlet’s father, or they glide; only Giselle is allowed feet, but as she flies, she trails them like a bird. The spirits of books and plays are imagined to exist in white robes whose folds must not be disarranged even by the most tragic emotion. They are like the aesthetic ladies of the eighties who had no waists and who were not permitted even to die except in a liberty pose.

‘Head’ 1952, oil

But how much more fearfully ghostly was this apparition that shook in every joint, whose enormous pale eyes were full of an excitement equally extravagant – whose very words sounded like the language of a world where meanings defeated any common syntax.

Startled, I began to get up. I could not make out what was happening, or if Wilde was speaking to me, only that he was staring at me and his stare was urgent. But at the same moment, he flung out his arms and plunged forward, knocking over a table of glasses and bottles with a crash which seemed to astonish and bewilder him. He stood gazing at the floor.

Win Davin then jumped up, touched his arm, and he went out with her. She came back in a moment, laughing, and said that Wilde had gone to bed. The broken glass was swept up, the carpet mopped, and the party went on as if nothing had happened; that is to say, in a general murmur of conversation which had no more reference to Wilde’s event than the rustle of garden leaves to a firework.

I had been ready to think the man drunk, but afterwards, when I was going away, Win Davin assured me that he was stone sober. The stare, the trembling, the strange sounds which resembled speech to the ear but not to the mind, were due simply to the shock of the unexpected, and a clash of ideas all insisting on immediate expression.

‘Rocky Landscape’ 1949, oil

Wilde was a painter who thought of himself as a Gulley Jimson in the world, and seeing me unexpectedly, he wanted to explain, all at once, his feelings about the book, about Gulley, about the relations of artist and public.

Since then, he has talked to me on all these matters, with the detached tentative air rather of polite conversation than obsession. He has, by nature, gentle manners, a soft voice, he is eager to agree with you – he has no idea of cutting a dash with startling opinions; he says what he believes, and what is true, and what is true is always a platitude.

We would agree quietly that a really original artist is never popular; that he always has had, and will have, a long fight for recognition; he is lucky to get it in his lifetime.

It is true that Wilde’s position resembles that of Gulley Jimson. In the trilogy, Wilshire is the conservative broken by the creative revolution; Gulley is the original creator defeated by conservatism. Gulley was an original artist and that means that he had no school, that he was alone.

‘Figures in Arches’ 1930-49, gouache

I do not mean by an original artist one who turns out variations of Picasso, Mondrian, Klee, Kandinsky, thirty or forty years after the prototypes. Imitators get plenty of appreciation. Critics are used to them and are not afraid to analyse and compare their works.

It is the painter who does not imitate, who is a true creator, who will have a long fight for recognition … [ … ]

I have often thought how true to the fact was that first apparition to me of Gerald Wilde, in the Davins’ sitting-room; he seemed like a revenant from another world of spirits, and so he was. He came to us out of a dream that he could not even describe, or explain – he could only paint it. For such a world, that realm where the original visual artist lives as naturally as we in our familiar conventions, is so alien to that of the judgement, of the critical reason, that judgement and reason themselves are barriers about it. A painter like Wilde is born to his own visionary dimension, and it is one necessarily so alien to his contemporaries, that it is equally hard for them to conceive it, or for him to describe it. [ … ]

I have lived now for some years with Wilde pictures, and I can vouch for the force of the novelty. And their impact is that of an original, a great art.

By an original art I mean one that adds to my visual imagination, a new dimension; by a great art, one that moves greatly and profoundly. [ … ]

You cannot classify Wilde’s art. It is not representative; and neither is it abstract. It conveys the most powerful impressions by means of form and colour of which the relation is not so much to an actual world of objects as to the real world of fundamental and universal experience.

I cannot explain what I feel before the grand and strange complex of Wilde’s Rocky Landscape, of his Green Seascape, of the landscape that he has never named, that I call the Woman on the Shore, or his Creature. But for me they belong emphatically to the category of great art. And they are profoundly original.