Arthur Berry in the early 1940’s

In 1942, Arthur Berry, a promising 17 year old art student from a Potteries working class background, was given the opportunity of a London visit by a benefactor and art buyer, a Mr Thompson. First stop was to be a visit to the National Gallery in the company of “two Scottish painters”, whom Berry, wearing for the occasion a hopefully bohemian trilby, awaited eagerly. The painters turned out to be the Two Roberts, Colquhoun and MacBryde, and the cultural visit turned rapidly into a Fitzrovian pub crawl. This account is excerpted from Berry’s highly readable autobiography of 1984, A Three and Sevenpence Halfpenny Man, reprinted this year by North Staffordshire Press. (This should really go on the Roberts’ page above, but that’s now getting a bit crowded, and will be reorganised in due course.)

A recent post on Mark Finney’s blog lists the drinking holes of wartime Fitzrovia as catalogued by Berry’s fellow Potteries painter John Shelton. The York Minster, the Fitzroy and the Bricklayer’s Arms, all visited on this occasion, are included; Shelton notes that the latter was nicknamed “The Burglar’s Rest”. He lists several drinking clubs, including the famous Colony Room, but this cannot have been the basement club visited here, given that the Colony is on the first floor. The trio’s meal may have been at the “Coffee An”, a disreputable late night eatery on New Oxford St.

Berry in his later years

At this time the Roberts were at a flat in St Alban’s Studios in Kensington, a high ceilinged room with a raised gallery and staircase (“a little balcony”, as Berry puts it) at one end. Berry writes well on the Roberts’ dress sense, and on MacBryde’s singing (even if he does spell him as “McBryde” throughout). Their paintings in the studio also clearly made an impression on him; the “smaller pictures of lock gates” are a clear reference to Colquhoun’s oil The Lock Gates, recently painted, exhibited in 1942 and 1943, and now in the Kelvingrove, Glasgow.

It’s not quite the case, as implied here, that Berry was never to meet the Roberts again, but by the time he caught up with them in 1945, he suspected that already their “talents were now beginning to show signs of being damaged by the bohemian life they were living.” It does seem extraordinary quite how much drinking went on in the middle of a war.

Berry admits freely to having been a bit naïve about homosexuality at the time, but even so it’s odd that he shows no sign here of realising that the two Roberts were an item …

* * *

… I saw two young men coming up the steps towards us. They were both in their late twenties and were dressed in what to me was a very bohemian way. Colquhoun had a long, handsome, bony face, with thick curly hair that grew down the back of his neck. He was wearing a cap and had a leather jacket on. McBryde had hair as black as liquorice and a round, high cheek-boned, Irish face. He was smoking a cigarette that hung from the middle of his top lip. Immediately, I felt the magnetism of their personalities. They were completely different from each other, yet were a perfect pair. Both spoke with rich, Scottish accents.

[After a short spell staring at pictures in the National, the three head off for a drink, starting at the York Minster (“the French Pub”), where they run into John Minton – “a thin-faced man dressed in a sailor’s jersey”, moving on to the Fitzroy and then to The Bricklayers in Charlotte Street, where Berry, not used to the pace of drinking, throws up in the toilets …]

The rest of the day was just a long succession of drinks. When the pub shut in the afternoon, McBryde led the way down some steps into a drinking club, which was a dimly lit cellar where the drinks cost twice as much as in the pub. The place was packed. At the top end of the tiny bar, a haggard-faced man with long hair and a cigarette holder was talking to a beautiful young girl who appeared to be drunk. As soon as she saw McBryde, she came over to him and kissed him. After the drinks had been bought, he started to sing again and as he sang, the company stood aside from the bar to watch him. I had never heard the song he sang before. It was about a girl called Lisa Lindsay who was about to be married but went off with the Lord Ronald McDonald instead. When he finished this song, there was a round of applause and drinks were bought for him, and he was prevailed upon to sing again. This time a Hebridean love lilt, a song which sounded sad and lonely and very far away from the club we were in.

[After more drinking, a confused café meal, at which he ruins a Vienna steak with excessive tomato ketchup, and a taxi ride back to Colquhoun’s and McBryde’s studio, Berry passes out.]

… when I awakened in the middle of the night, I’d got all my clothes and my shoes on and was lying on what felt like a camp bed against a small stove. I could hear someone snoring, and when I raised myself up, I could see the shape of a figure lying face to the wall on the other side of the studio. I could tell it was a studio by the big window that covered one side of the room … The sleeping figure, I could tell by its shape, was Colquhoun. I wondered where McBryde was sleeping, then I heard someone cough and saw a little balcony above my head and realised he must be sleeping up there …

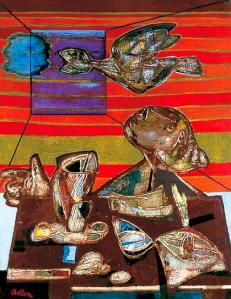

Then suddenly I heard McBryde start coughing and get out of bed. A moment later, the light went on and he came down the stairs from the little balcony and went through the door. In a second or so, I heard the lavatory flush, so I got out of bed and went to relieve myself. I thought I’d never been so glad to have a pee in my life. McBryde, who I knew by now was called Sasha, didn’t go back to bed but made a cup of tea and lit a cigarette and began laughingly to go over what had happened last night. He said we’d all been drunk when we got back to the studio. This came as a tremendous relief to me as I’d imagined I was the only one in that state. Then Colquhoun began to get up and pulled the blackout blind up from the studio window. It was daylight outside and McBryde gave me a toasting fork to toast some bread. The studio was small and had two easels on a raised platform. On both of them there were half-finished pictures. The pictures were like nothing I’d ever seen before. They were cubist in the way they were structured, but had very distinctive colouring – mustard yellow and deep earthy reds. As I looked closer at them, I could see the images were of peasant-like figures with heavy faces split up in many places. Then I noticed some smaller pictures of lock gates and one still life of yellow citrus fruit. I didn’t know what to make of them or what to say as I sat drinking tea, while the two Roberts got dressed. Sasha, the very dark one, put a kilt on and a black shirt with a light-blue bow tie, while Colquhoun was pressing his trousers. They were both very particular about how they looked and dressed very elegantly in an artistic way, in clothes that seemed to suit their personalities perfectly.

[That day Colquhoun and Berry meet Mr Thompson, Berry’s benefactor, at the Savile Club, where Berry suffers from some social embarrassment. Berry and Thompson move on to an appointment with Jacob Epstein, bidding farewell to Colquhoun.]

Colquhoun … said good bye and walked off towards Bond Street. I felt sad as I watched him, for although I’d only known the two Roberts a few hours, I knew I’d never met anybody remotely like them and never would again. They were from a bohemian world I’d never realised existed – a world far more exciting and dangerous than the one I lived in, a world where you lived from day to day and drank without remorse. It was what I imagined the Paris of Modigliani and Soutine had been like. I didn’t realise then it was a world you didn’t grow old in.