I’m long overdue settling my confused account of the oddly varied work of painter and illustrator Stanley Jackson, as promised back here. Apologies to all involved. For previous episodes, see here and here, but rather than add bibs and bobs at this point, it seems better to lay out the whole thing afresh and refer back sparingly. Mainly because, as previously noted in passing, it turns out that there were two Stanley Jacksons, whose stories show some striking coincidences. To the extent, in fact, that at one stage in our investigations the descendants of one Stanley were pretty much convinced that both might have been the same person. But it wasn’t so … Let’s call them Stanley One and Stanley Two. As we retrace their lives, in many ways quite different, some strange points of convergence may emerge.

Stanley One

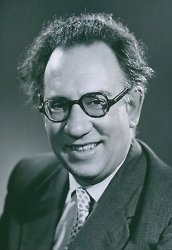

Self portrait [Courtesy Jackie & Eloise Hendrick]

Stanley Arthur Jackson, painter, commercial artist, newspaperman and advertiser, was born in 1910, though he was later to claim that his birth year was 1917. Vanity? Perhaps. An undated self portrait, apparently done in the ‘thirties, shows a confident, almost raffish, young man in a dark overcoat and white polo neck, gazing out steadily at the viewer. [Click all images to enlarge.]

We tend to assume that, war service excepted, the lives of our twentieth century forebears were pretty static, but in fact, for those with the need or the inclination to wander, the British Empire provided an early form of globalisation, with ready opportunities to uproot and begin again. And Stanley Jackson, a man clearly with both drive and charm, was never one who was afraid to begin again.

-

-

Stanley Jackson in his India days [Courtesy J & E Hendrick] …

-

-

… and in South Africa

In the ‘thirties he worked in India, and from 1937 was General Manager of the Madras

Mail, overhauling and expanding its advertising. In 1942 he was appointed Director of Public Relations to the Joint War Organisation in India, creating publicity campaigns employing press, radio and film. His surviving paintings of Indian subjects were done during this time: the National Army Museum has a cheerful 1943 painting of a Madras infantryman, while Nuneaton Museum & Art Gallery has an undated oil of Madras boat builders, attributed to an E Jackson, but in my humble opinion by our man. (The identity of this painting has been the subject of an extremely protracted discussion

on the Art Detective site, here.) These works are highly competent, the style chunky, with a warm, almost romantic feel.

-

-

Madras Guardsman [National Army Museum]

-

-

Madras boat builders [Nuneaton Museum]

At the close of the war in 1945 Jackson moved to London, working at Lintas advertising agency creating campaigns for soap brands, but two years later moved to South Africa and with his first wife set up his own business, the S & J Jackson advertising agency, Johannesburg. His commercial art of the period is fluent, highly styled, very much of its time. (Celrose, a Durban clothing manufacturer, is still in business today, incidentally.) Following his wife’s unexpected death Stanley Jackson remarried in 1950, sold up and returned to the UK, but before long was separated and on the move again, this time to Hong Kong.

-

-

[Both courtesy Jackie & Eloise Hendrick]

-

From here the trail gets more than a bit hazy, but there are glimpses, albeit in different continents: we know that Jackson created murals at the Hong Kong Club and at some point was commissioned to paint a portrait of Chiang Kai Shek. Later in the ‘fifties he was in Kenya, and later still in Bangkok, where he married for a third time and raised a new family. In the ‘seventies he worked for a newspaper in Canberra, Australia. He died at some point in the ‘eighties. An attractive painting from the Bangkok period, a lively, golden Thai dancer, turned up for sale recently in New Zealand. It has a touch of the psychedelic.

[Courtesy Jim Rowe]

There’s certainly a great deal more that we don’t know about Stanley One, a man of the world whose restless self-reinventions would make, as his granddaughter Eloise says, a great movie. I’m most grateful to her and to Stanley’s daughter Jackie for their help in pinning him down at least a little.

Stanley Two

Stanley Jackson, painter, commercial artist and writer, was born in 1917. (My thanks to Oliver Perry for unearthing a brief Who’s Who in Art entry for him.) He was schooled in Ongar and studied art at St Martin’s. His paintings – many apparently landscapes and townscapes – were exhibited quite widely in the late ‘thirties and early ‘forties, including at the RA.

Two watercolours with gouache, views of Edinburgh and Canterbury, sold at Toovey’s, the Sussex auction house, a few years back, fetching just £20 the pair. Jackson’s style is analytical but crisply confident; despite the mundanely picturesque subjects, the strong tonal planes owe much to post-cubism – there is a modernist lurking in here. On a rather different note, but recognisably by the same hand, is a painting of wartime refugees, the single Jackson item to show up on auction value sites.

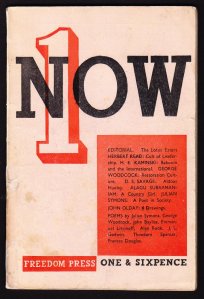

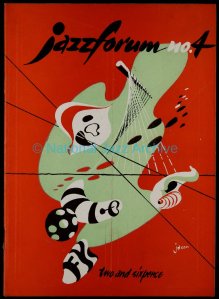

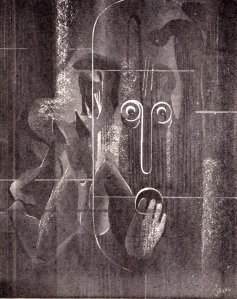

Jackson also had an income as a commercial illustrator, including for children’s books; his cover for May Wynne’s Little Brown Tala Stories suggests a strong yearning for imaginary worlds. From 1944 this found a sudden and startling flowering in his covers for jazz publications written or edited by Albert (AJ) McCarthy of the “Jazz Sociological Society” – Jazz Forum, Jazz Review, Piano Jazz and publications by Jazz Music Books. The ambience of McCarthy’s jazz coterie was strongly literary and experimental, and in these images Jackson lurches abruptly into surrealist semi-abstractions, which found their ultimate bongoid flowering in his “Pattern of Frustration” series reproduced in black and white in George Woodcock’s anarchist literary review Now in 1944.

McCarthy’s write-up for “Pattern of Frustration” announced Jackson’s “withdrawal from the academic field towards a personal maturity which can only be expressed in less rigid forms.” That puts it mildly. I’ve re-gathered the images here, but McCarthy’s full text can be read

in my first Stanley post, while Jackson’s own feverish artistic credo – “Everlasting layers of ideas, feelings, images, images which madden, which terrify, which intoxicate, images which sob” – can be read in full

here, in my follow-up post.

-

-

Awareness

-

-

Phase of Introspection

-

-

The Exquisite Moment of Scintillation

-

-

Ultimate Despair

Clearly, Jackson had toppled headlong into Bohemia and avant-gardism. However, at this point the bonkers abstractions suddenly disappear as his career veers off at right angles. In 1946 he married Ruth Pearl, a professional musician of real standing, the first woman to be a concertmaster of a professional orchestra in Britain and, until 1949, the leader of her own English String Quartet, a favourite of Vaughan Williams. That year she and Stanley moved to New Zealand where their son was born and where she thrived as a concert soloist, while Stanley did – what?

One of Ruth’s obituaries describes him as “a musician and artist who made a living as a commercial artist and music teacher”. Despite his jazz connections, I’m unsure about the music bit, as a quite different Stanley Jackson, organist and music teacher, was active in New Zealand then and beyond our Stanley’s death, which suggests a possible confusion. Three landscapes by Stanley Two are noted on Australian auction record sites, where he is down as “working 1950s” but unlisted in the standard sources; beyond that, I’ve found nothing. Stanley Jackson died in 1961 in New Zealand. His wife Ruth remarried, continued her career and died in 2008; her obituaries can be found here and here.

The Stanley convergences

At one point in this enquiry, I suspected that the apparent level of coincidence between the Stanley stories might be no more than my way of lending dignity to my own confusion, but then again …

To summarise: both Stanley Jacksons were born, or claimed to have been born, in 1917. Both were fine artists, commercial artists and writers. Both were in or around London during 1945 to 1947, and for all I know might have brushed shoulders on the Tube. Both then left the UK for new lives and new families in distant parts. Postwar, both lived and painted in the Antipodes. (The late emergence of a painting by Stanley One in New Zealand, where Stanley Two relocated, flung a particular spanner in the works!)

-

-

SJ One

-

-

SJ One

-

-

SJ Two

-

-

SJ Two

Observant readers will have spotted that the chunky lettering of Stanley One’s signature is quite different to the usual sharp italics of Stanley Two’s. However, they may also have noticed that it’s not totally incompatible with the “Jackson”, “Jaxon” or “Jxn” signatures of Stanley Two’s loopy period, a resemblance that threw me for a bit. (One distinguishing oddity is that Stanley Two seems to have signed his full name, at least on occasions, minus the “e” in “Stanley”, though in print he is always referred to as “Stanley”.)

Common to both their stories is the theme of repeated renewal, removal and reappearance, the reinvention of self. What creatively extraordinary lives some people have lived!

Finally, I’m still uncertain as to which of our two Stanleys may have been the author of

An Indiscreet Guide to Soho, an obscure but racy little volume of 1946 that today is a bit of a cult buy. The blurb describes the author as “a master of the art of reportage” who “knows his Soho intimately and has lived in this colourful area”. Stanley One, newspaperman and advertising copywriter, seems at first glance the likely candidate, but then again Stanley Two’s Bohemian-jazz connections might suggest a deeper acquaintance with the pulsing wartime nightlife of the quarter, and he certainly could write. Both were in the right area at the right time, so it must have been one of them, surely?

Unless, of course, there was a third Stanley Jackson prowling the alleyways of Soho, perhaps alternating his masterful reportage with the occasional painting or illustration … If there was, please let me know!