The ‘Betty’ letters

As well as interesting marginalia, a bonus of buying second hand books is finding unexpected stuff tucked between pages, so I was chuffed recently on acquiring a set of the early ‘fifties poetry review Nine to find various fliers and cuttings hidden within, plus three letters to the original owner of the magazines from the classical scholar, translator and academic W F Jackson Knight (brother of literary critic Wilson Knight). One of these throws an interesting light on the methods of Nine and of its pugnacious and reactionary editor, the poet and self-appointed disciple of Ezra Pound, Peter Russell.

Eleven ‘Nines’

The letters are to a “Betty”, probably an ex-student of Jackson Knight’s (though not, as I first thought, the classicist Betty Radice, later an editor at Penguin Classics). “JK”, as he signed himself, maintained a vast correspondence with ex-students and others, so it’s annoying but hardly surprising that my unidentified Betty makes no appearance in Wilson Knight’s exhaustive and exhausting 1975 biography of his brother, which I now plan to employ as a doorstop or flower press.

Much of the contents of the letters is shrill and slightly flirty chatter (JK never married), but in February 1950 he wrote to acknowledge a letter that Betty, who clearly had some close association with Nine, had inserted with a prospectus for the review:

“Naughty to put a letter in for 1d! How I liked it though. I wishd you were here.

Can I, if I subscribe, have the first issue of NINE? What chances to keep it going? Can you work together with The Wind and the Rain and be the Criterion, and get safer – you two the only two? What hope of getting hundreds and hundreds of my little friends into nine-print? No – only good ones, who deserve it – and only the pieces which should be printed. I don’t care about just another mag. I do care about the right one (prospectus looks good), which really serves the right causes and above all the divine niceness and brilliance of the sort of people you and I know who we mean by which. Grammar OK?”

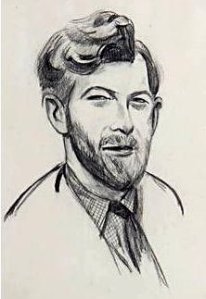

‘JK’ in the early ‘fifties

JK’s letters, wrote Wilson Knight, “drive the informality of epistolary writing to the limit.” No doubt Jackson Knight wrote as he spoke; it’s always a slight shock to realise that some people of a certain class really did talk like this. The Wind and the Rain, a rival literary review run by Neville Braybrooke, had recently printed a piece by Jackson Knight on his favourite author, Virgil. He did indeed go on to subscribe to Nine, to which he was also to make a single ill fortuned contribution. So was Nine to prove the right sort of mag, serving the right causes, and run by the right sort of people? Well, it was “right” in one sense.

“The Right is to-day, everywhere the Underground Resistance!” shouted Peter Russell in issue 2 of Nine. Reacting to what they saw as a poetic decade of undisciplined and introverted Leftist neo-romanticism, Russell and his editorial board – poets G S Fraser and Iain (later Ian) Fletcher, editor and classical translator Ian Scott-Kilvert and classical critic D S Carne-Ross, afterwards a Third Programme producer – banged the drum for a return to objectivity, order, tradition and form. In this post-war re-invigoration of the great literary tradition, translations from the Classics were to play their part. Even so, Nine was happy to print poems by Charles Madge, Ronald Duncan, George Barker and others positioned well outside its programme, though it was not always an unstrained fraternisation. For Russell, if not for his co-editors, these literary standards were of a piece with his maverick political rightism.

Peter Russell, drawn in 1950 by Wyndham Lewis

In the event, it wasn’t too long before the wheels fell off. Issue 1 of Nine had appeared in the Autumn of 1949. Oddly, all but one of the editorial board vanished abruptly from the title page after issue 7 of Autumn 1951, leaving Russell to manage the final four issues solo. What happened?

His ‘seventies collaborator William Oxley later recounted Russell’s version of the crash, given twenty years afterwards. Two highly unpleasant reviews by poet Roy Campbell, loose cannon and elder statesman of the maverick right, had “blown apart” the board; one of a book by Stephen Spender, the other of:

“… some translations done by an eminent professor of whom Campbell wrote: ‘We do not expect poetic talent from a translator, let alone a professor, but we are entitled to insist on elementary scholarship.’ The editorial board of Nine, apart from Russell himself, were ‘all aspiring professors looking for safe jobs in universities,’ and they refused to countenance the publication of Roy Campbell’s offensive review.”

This “offensive review”, of J B Trend’s translations from the Spanish of poems by Juan Ramon Jimenez, eventually appeared in Nine 9, with a note by Russell explaining that it had been rejected by “the then editorial board”, and first printed in The Catacomb, the scurrilously reactionary (and loss-making) review run by Campbell and his son-in-law Rob Lyle, but bailed out by Tate and Lyle sugar money – “catacombs financed by saccharine,” as Christopher Logue put it.

“Though it is difficult to imagine what literary motive can have prompted the publication of this book,” fumes Campbell, “the political motive sticks out a mile.” His “review” then veers off into the familiar Campbell rant about the Spanish Civil War, “gun-shy poets” such as Auden and Day Lewis, the Iron Curtain and so on. It’s not hard to see why the board had cold feet.

On top of all this Russell’s co-editors, their suspicions aroused by an unpaid printer’s bill, had accused him of having his hand in the till, while a fire destroyed the contents of Nine’s office in 1951, postponing issue 7. Thereafter frequent appeals for renewals of subscriptions couldn’t prevent disastrous delays to later numbers. Nine finally gave up the ghost in April 1956.

‘… the MS was altered …’

But there may have been other behind-the-scenes unpleasantnesses that contributed to its break-up and decline. One is disclosed by Jackson Knight in a later letter to “Betty”:

“Re P[eter] R[ussell] – I did draw back a little. I didn’t seem to be much wanted. And when I’d done something asked of me actually during a week end of hundreds of miles, arduously, the MS was altered to make me disapprove when I’d approved of something – rewritten. So I couldn’t sign it. I don’t know if it was printed. I’ve never had this happen in 33½ years otherwise. I am not cross. I know something of the literary fight and literary code. I just keep away when I can, having seen the way the wind blows. Yet I received a N[ine] actually today.”

The “something asked of me” was a review of half a dozen Penguin Classics translations; this did appear in Nine 6 (Winter 1950-51), but under the pseudonym “Classicus”. (Clearly Knight was never sent a copy.) The books he had reviewed included two prose versions by E V Rieu, co-founder and editor of Penguin Classics, Homer: The Iliad and Virgil: The Pastoral Poems. (Rieu’s previous, ground breaking Homer translation, The Odyssey, had been the opener for the series.)

The offending article

Of the Virgil, “Classicus”/Jackson Knight approves most warmly: “ … as felicitous as any modern English prose version .. can be expected to be … The most fastidious reader … will find nothing to blame.” And “Classicus” even heads off the predictable charge of dumbing down: “If this is ‘culture for the masses’ – and I think it is – we must have more and more of it …” All the other books are thoroughly approved, except for one, Rieu’s Iliad.

Here his opinion appears inconsistently damning: “Homer is eminently rapid, eminently plain and direct, and eminently noble … Dr Rieu’s prose Iliad satisfies the first two conditions … but fails to satisfy the third. Of the supreme grandeur of his original he manages to convey very little …” And that’s about all “Classicus” has to say on the book. This has to be the section altered by Russell to censor Knight’s original, more generous approval of Rieu’s Iliad. But why?

In our post-Classics culture it’s not easy to appreciate just what was at stake, and how threateningly communistic Rieu’s approach might appear to some. As Sun Kyoung Yoon explains in a 2014 article in The Translator:

Rieu … translated Homer in an egalitarian spirit, in line with a trend which was gaining ground in the aftermath of the Second World War. To bring Homer to the widest possible range of readers, Rieu chose to transform his epics into novels … emphasising narratives and characters … his Odyssey, in particular, was a major landmark in popularising the Classics: the huge success of Rieu’s Penguin edition proved that Homer could be made accessible to anyone.

Popularised perhaps, but hardly popular with Peter Russell. In a stand-off between accessibility and “grandeur,” his elitist instincts knew no doubts. The issue of Nine that carried the censored review by “Classicus” also promised forthcoming numbers on Latin and Greek literature, “to re-establish creative contact with the past.” Translations were solicited that should not “sacrifice poetic vitality to accuracy, nor accuracy to poetic vitality.” For Russell, Rieu’s egalitarian translations met neither criterion. In the event these special numbers did not materialise; in humiliating Jackson Knight by tinkering politically with his review, Russell made sure of that.

Popularised perhaps, but hardly popular with Peter Russell. In a stand-off between accessibility and “grandeur,” his elitist instincts knew no doubts. The issue of Nine that carried the censored review by “Classicus” also promised forthcoming numbers on Latin and Greek literature, “to re-establish creative contact with the past.” Translations were solicited that should not “sacrifice poetic vitality to accuracy, nor accuracy to poetic vitality.” For Russell, Rieu’s egalitarian translations met neither criterion. In the event these special numbers did not materialise; in humiliating Jackson Knight by tinkering politically with his review, Russell made sure of that.

But we are in Cold War territory here. And the fracture lines of the times were as liable to appear in the pages of the little magazines as anywhere else, as this minor classical spat demonstrates.

Recommended as a flower press

Jackson Knight died in 1964, his reputation as a scholar and a gent unblemished, apart from an enthusiasm for spiritualism that led him to consult the shade of Virgil himself to advise on his 1956 Penguin translation of The Aeneid, the “Supreme Poet” even dictating answers to JK’s questions directly in Latin to his medium Theo Haarhoff; in séances Virgil appeared to Haarhoff’s niece clad in his laurel crown.

Peter Russell died in 2003 after a long, hugely prolific and generally penniless career as a professional poet. His later work, under the influence of his “mentor” Kathleen Raine, moved away from the vaunted objectivism of the Nine years to a gushy, “vitalist” and often confessional Neoplatonism. His anticommunism never wavered.