Satan disguised as an engineer, a madman in the attic, an army of radioactive Welsh miners, plus Cinderella … Yes, it’s British anarchist drama of the ‘forties! This post will be a little longer than usual, I’m afraid, so be patient. First, a quick recap on the origins of all this in the poetic dramas of the previous decade.

The new poetic theatre

Plenty has been written elsewhere about the ‘thirties heydays of the “new poetic theatre,” and in particular the plays, more or less political and Brechtian, of W H Auden and Christopher Isherwood, staged by Rupert Doone and the Group Theatre with the incidental music of Benjamin Britten, the sets of Robert Medley, and Faber to publish the scripts – quite a back-up! The first of these, The Dance of Death (1931), an Auden solo effort, is somewhat clunky but finishes splendidly with a brief guest appearance by Karl Marx:

Plenty has been written elsewhere about the ‘thirties heydays of the “new poetic theatre,” and in particular the plays, more or less political and Brechtian, of W H Auden and Christopher Isherwood, staged by Rupert Doone and the Group Theatre with the incidental music of Benjamin Britten, the sets of Robert Medley, and Faber to publish the scripts – quite a back-up! The first of these, The Dance of Death (1931), an Auden solo effort, is somewhat clunky but finishes splendidly with a brief guest appearance by Karl Marx:

Announcer. He’s dead.

[Noise without]

Quick under the table, it’s the ‘tecs and their narks,

O no, salute – it’s Mr Karl Marx.

[Enter Karl Marx with two young communists]

KM. The instruments of production have been too much for him. He is liquidated.

[Exeunt to a Dead March]

THE END

Auden and Isherwood’s The Dog Beneath the Skin (1935) is my favourite of the series; their fascist-infected English rural idyll of Pressan Ambo, closely related to the nightmare delusions of Edward Upward’s extraordinary 1938 novel Journey to the Border, blends banality with menace, and is a fine satiric invention. In comparison The Ascent of F6 (1936) and On the Frontier (1938) seem to lose a little sparkle.

Auden and Isherwood’s The Dog Beneath the Skin (1935) is my favourite of the series; their fascist-infected English rural idyll of Pressan Ambo, closely related to the nightmare delusions of Edward Upward’s extraordinary 1938 novel Journey to the Border, blends banality with menace, and is a fine satiric invention. In comparison The Ascent of F6 (1936) and On the Frontier (1938) seem to lose a little sparkle.

Not surprisingly, other McSpaunday personnel get in on the act: Louis MacNeice’s witty Out of the Picture (1937) or Stephen Spender’s execrable “tragic statement” Trial of a Judge (1938), both also realised by Doone and Faber. Somehow Spender manages to write an anti-fascist play in which the fascists are the only interesting characters. One can almost forgive them for locking up opponents who go on like this:

TWO RED PRISONERS.

Your days in dark, our dark that wakes,

Across the centuries and the waves

Will join to break our chains and break

Into the nobler day which saves.

And so on. And on. John Piper’s scenery was wasted on it.

The coming of war and the dissipation of that particular political-poetical consensus might appear to mark the end of these theatrical experiments. So it’s interesting, a decade on, to come across their minor progeny under the colours of anarchism, which in more or less individualist or philosophical shades had become the ideological flavour of ‘forties neo-romanticism. Here are two examples.

The Last Refuge

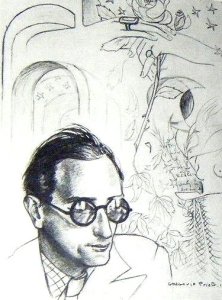

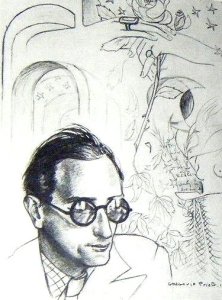

Wrey Gardiner by Gregorio Prieto

The more slight, but no less interesting, is Wrey Gardiner’s The Last Refuge, a single act affair that pops up in the 1945 edition of New Road, an annual neo-rom anthology published by Gardiner’s own Grey Walls Press, and edited at the time by Fred Murnau. Charles Wrey Gardiner was most active as a poet and autobiographer, but is better remembered for Grey Walls and for his sustained editorship of Poetry Quarterly. Whatever the strength of his sympathies, The Last Refuge seems to be an unusual instance of his nailing his black flag overtly to the mast.

The play must have been written a few years before it saw the light in 1945. Despite some minimal stage directions it’s maybe better considered as unperformable, a drama on the page in the manner of Gervase Stewart’s The Two Septembers, or Robert Herring’s “pantomime” of the Blitz Harlequin Mercutio, to give two others from the same period and sampled on this blog. Virtually the entire script is versified. The action (or conversation, mostly) is set in a bombed-out house deserted by its owners, emblematic of Blitzed England, and squatted by a selection of archetypes: an Old Woman, her earth-daughter Cinderella, a Lunatic (her traumatised son in the attic), and an Anarchist who ascends from the cellar. A Voice in the Air from a wireless interjects occasional propaganda and inane dance music. Visitors comprise a Poet, in love (inevitably) with Cinderella, and an Inspector, the embodiment of authority, come to arrest the squatters on a charge of “living dangerously.”

The few moments when Gardiner tries a satirical touch are uncomfortably clumsy: “Silvery Sid and his Sauntering Saps” is not a great mickey-take name for a radio dance band, and Cinderella’s unsophistication at times has a cor-luv-a-duck touch – “Did ever anyone have such funny men as come my way?” The writing is far happier when Gardiner goes with his usual (and rather likeable) overstrained earnestness. The central tension here is between the writer’s twin, dialectical self-projections, the Poet and the Anarchist, the Poet being apt to rhapsodise in gloomy symbols, provoking the Anarchist’s denunciation:

Your song is vague and indecisive, Poet.

What the poor people need is freedom,

Not the undying words of a dyspeptic dream

But a bitter marching song that none can stem,

A rising tide, a rousing fire,

An anthem for the world’s despised.

Where the poet sees the traumatised son as “a caged animal” the Anarchist hails his insanity as a liberation:

He has had that little jolt

That brings a man to know

His own will’s the source and fountain

Of his own world.

The second bomb would give him the full knowledge

Of one who walks and lies down at will,

Accepts and refuses the snags of fate,

Free in a world where mass suggestion has no power.

The Anarchist brings proceedings to a sort of conclusion when, in a moment of Stirnerite resistance, he grabs the poker from the fireplace and brains the Inspector, leaving the Lunatic to pontificate –

All you poor crackbrained fools who disdain desire

Are but the slaves of a crawling cesspool

Some call sanity.

– the Poet to ruminate –

Truth is still stranger than we know,

Like light falling in a chaotic dream

In the twisted corridors, suddenly upon the wall,

Haunting the mad, the suffering, the chosen few.

– and Cinderella to round it all off with a nice bit of bathos:

Love as a woman’s tear will always fall

Sure as the gentle rain upon us all.

It’s all agreeably heady, and very much of its moment.

Cities of the Plain

If the class solidarity of “the world’s despised” is only alluded to in The Last Refuge, it’s up front, with marching boots on, in our second contribution, Alex Comfort’s “Democratic Melodrama” Cities of the Plain, published by – who else? – Grey Walls Press in 1943. As poet, novelist, literary critic, anarchist theoretician and conscientious objector, Comfort was remarkably busy during the ‘forties, with a literary reputation later eclipsed by his Joy of Sex fame. (Cities had been preceded in 1942 by Comfort’s “mystery play” Into Egypt; as this is currently unobtainable, I can’t say anything about it.)

If the class solidarity of “the world’s despised” is only alluded to in The Last Refuge, it’s up front, with marching boots on, in our second contribution, Alex Comfort’s “Democratic Melodrama” Cities of the Plain, published by – who else? – Grey Walls Press in 1943. As poet, novelist, literary critic, anarchist theoretician and conscientious objector, Comfort was remarkably busy during the ‘forties, with a literary reputation later eclipsed by his Joy of Sex fame. (Cities had been preceded in 1942 by Comfort’s “mystery play” Into Egypt; as this is currently unobtainable, I can’t say anything about it.)

If Last Refuge was not designed for performance, Cities most certainly was. A slightly pompous permissions note states that the author “wishes to repudiate in advance all the ideological constructions, of whatever complexion … placed upon this play. Ideological theatres will apply unsuccessfully.” Whether any theatre, ideological or not, applied successfully to stage it, is an open question. Directions insist that it is to be acted “with the maximum of gusto.”

A remarkably schoolboyish Alex Comfort faces up to the shadows of the mid-forties

The play, closer to its Auden-Isherwood predecessors, is set in a parallel society. The title references the Sodom and Gomorrah of Genesis, but the narrative involves a single unnamed city in thrall to a ruthless capitalist corporation that mines the neighbouring mountain. (For some reason best known to Comfort, the miners have Welsh names: Iorwerth, Dai etc.) Facing imminent bankruptcy, the directors sell out to a proposal by two mysterious and unscrupulous “Engineers” to mine the mountain for radium; though many miners will die from radioactivity, this is presented to them as a noble and necessary sacrifice. Dissent is encouraged by the principled doctor, Manson (man’s son, presumably), who leads back from the mountain an army of scorched, ulcerated and mutated miners who tramp off into the future, members of the audience joining them, to lead the revolution.

While the majority of characters are believable to degrees, the two Engineers operate on a different level. The Black Engineer, so called for the colour of his clothing – black shirt, velvet dungarees and biretta – is revealed as something beyond human when he encounters the sherry quaffing Bishop of Sodom and Gomorrah (a “pillar of Conservative-Churchmanship”), who recoils in horror, crying: “I don’t believe in you! I’m not a Manichee! You’re a heresy!”

This odd disjunction is a deliberate dramatic contrivance. In a discussion on Shelley’s The Cenci in “The Critical Significance of Romanticism,” later collected in his 1946 Art and Social Responsibility, Comfort notes that in that play, as in those of Ford and Webster:

The human players pass through a tragic conflict, but their opponents are not persons – they are naked, animated symbols. The impulses and powers of evil and of infatuation which in tragedy operate through imperfect living people are here made external and come to occupy whole persons, elevated to the same status of identity and reality as the protagonists … [Cenci] is a mask, as if the Devil had inspired a dummy or a suit of armour and made it walk.

The human players pass through a tragic conflict, but their opponents are not persons – they are naked, animated symbols. The impulses and powers of evil and of infatuation which in tragedy operate through imperfect living people are here made external and come to occupy whole persons, elevated to the same status of identity and reality as the protagonists … [Cenci] is a mask, as if the Devil had inspired a dummy or a suit of armour and made it walk.

Here is the Black Engineer’s offer to the Directors, in return for the mountain:

I offer you the price of your living, to drink the wine of this plain and to sit at this table – to sleep with your wives and to keep your names out of the papers; to make the sun and the moon stand still in the sky, and to sanctify the status quo. I offer you a new grip on the reins, a new leg for your broken chair. You shall not become bankrupt but be rich, and you shall die and lie in gold coffins …

It’s remarkable that the atheist Comfort, in order to personify and animate corporate evil, is obliged to fall back on this Faustian religious supernaturalism.

Like Auden and Isherwood, Comfort keeps his verse passages for key moments and uses far more vernacular conversation than Gardiner, though this can be a bit overdrawn and heavy handed at times. With the possible exception of the miners’ songs, which have a passing touch of Disney’s Seven Dwarfs (“With a will, ho!”), the verse is effective. Comfort was, in fact, a pretty decent poet. Here’s some of Manson’s big speech at the end of Scene II, pleading for the healing of the sick earth:

Now in the night, when continents

like tables cool and creak, and each tap’s timbrel

flickers invisible, constellations rise

westward on Europe moving carefully.

Out of Orion’s cockpit with no noise

the white aseptic stars watch blind earth tossing,

clawing the mask, going under; see the rivers’

reflexes quietly fade, the body grow quiet.

Between the hems of night the inflamed cities

throb in the flank; the finger in wise pity

probes the soft coils – as the stars’ gloved hands

draw up the wounded countries with small stitches.

You of the lancets, Sirius, Betelgueuse,

scanning the festered cities, plotting the fever,

cut to the permanent bone. This sickness is mortal.

Incise the will. Restore the healthy granite.

As a bit of a contrast, here’s the feverish, apocalyptic dance of the revelling shareholders, sung as the miners march to their fate, with a touch of Louis MacNeice’s “Bagpipe Music”:

The hills are tumbling round our ears,

The stars crash down from the night;

But the bonds are good and the wheels go round

And there’s wind in the bagpipe yet.

Seven red madmen dance to the moon,

Seven pale horses rode,

But spades are trumps and the sun stands still,

And there’s wealth on the turn of the card!

Their wheels are broke and their bones are dry –

Their hammers bang for the coffin;

But all we see is a five-pound note

And a Union seat in the offing.

And grey death hides behind the door

With a rattle of shot in his throat,

But the wheels go round and the people roar

To keep the bastard out.

Can you hear the crash of the steeples, boys,

And the guns go crack in the trees?

The world shall burn to warm our hands –

It makes a lovely blaze!

There is more of value in this play, and much more could be said about it. But I will return at some point in these posts to Comfort’s poetry. He wrote two further plays. The first act alone of The Besieged appeared in Life and Letters Today for April 1944, but it was never published entire. Gengulphus is also listed as unpublished; some sources give a date of 1948, suggesting a possible publication, though I can find no trace of that.

The quick fade to these experiments in anarcho-drama is probably attributable to the same factors that saw off neo-romanticism in general. The verse speeches, the heightened, symbolic characters, the open calls to political action, the almost expressionist intensity – these are worlds away from the kitchen sink social realism of ‘fifties theatre.

It would be interesting to know if either of Comfort’s two published plays was ever staged. My ex-library copy of Cities (Croydon Public Libraries) sports a fully clean borrowing label; clearly Croydon Rep didn’t jump at the chance to put on this “Democratic Melodrama.” Which is rather a pity.